|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

work 2

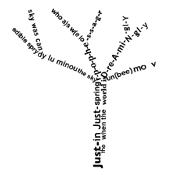

The Sweet Old Etcetera, by Alison Clifford (United Kingdom), 2005

The Internet, without a doubt, has opened up new spaces for literature, not only by increasing the number of pages available to it but also, more interestingly, by providing new expressive possibilities: interactive literature, multimedia, generative and participative literature, etc. We might say that a new narrativity is taking shape, one that is turning all our previous ideas about fiction upside down. The CIAC magazine has, moreover, already discussed this phenomenon in part.

The Internet, without a doubt, has opened up new spaces for literature, not only by increasing the number of pages available to it but also, more interestingly, by providing new expressive possibilities: interactive literature, multimedia, generative and participative literature, etc. We might say that a new narrativity is taking shape, one that is turning all our previous ideas about fiction upside down. The CIAC magazine has, moreover, already discussed this phenomenon in part.

Nevertheless, the form of literature which has most benefited from the new possibilities offered by digital technology and its dissemination on the Internet is certainly poetry. Not only because many poets have found in it a new way of disseminating their work, one that enables them to correct the deficiencies of traditional publishing in this field but because, much more importantly, the most contemporary poets finally have at their disposal production and distribution tools which enable them to fulfill some of the dreams of their predecessors. The state of technology, in their day, made it possible to produce only relatively rudimentary approaches which fall short of what is expressively perceptible in the work with which we are familiar.

Alison Clifford is not a poet; she is a media artist living in Glasgow, Scotland who asked herself what kind of texts a poet such as Edward Estlin Cummings (e.e. cummings) might very well to produce today with the available technology. Of course, such a project is risky, because only cummings could reply to such a question and we have no way of knowing his answer. Still, it is a good idea: cummings' work contains considerable "visual" temptations, in particular in his use of typography (non-standard use of brackets, the lack of space between words, the use of the page as a space open to the movement of letters which often become highly autonomous, the cutting up of words into separate letters, deliberately non-standard punctuation, etc.). On this level, his work was no exception in the early twentieth century (cummings was born in 1894 and died in 1962), which saw the publication of numerous "graphic" works by poets, whether they be Mallarmé, Apollinaire, Leiris or Seuphor in France, the Italian and Russian Futurists, the Spatialists, the concrete poets, Brazilian poesia processo, or more difficult to classify artists such as Ian Hamilton Finley. Of all this early twentieth-century bodies of work, cummings' is perhaps the one most actively searching for an "impossible to find" movement in that definitive and fixed medium, the book.

This search is perhaps most evident in a poem such as:

r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r

who

a)s w(e loo)k

upnowgath

PPEGORHRASS

eringint(o-

aThe):l

eA

!p:

S a

(r

rIvInG .gRrEaPsPhOs)

to

rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly

,grasshopper;

a text by its very nature indecipherable if we do not decipher the constant, erratic and unfathomable movement of the grasshopper, which cummings, if he wants to seize its essence, can only express through leaps from one word to the next which upset our lines of perception. The "translation" of this poem by Alison Clifford is remarkable because of what it reveals to us about it. I will leave you with the pleasure of discovering it for yourself.

In The Sweet Old Etcetera, Alison Clifford proposes, therefore, quite simply to introduce movement and, perhaps even more interestingly, the reader into this movement. The reader, according to her choice of one direction or another, unfolds the poem while occupying for a rime one of the possible places of the poet himself. Using some of cummings' poems, she creates dynamic and interactive picture-poems. The presentation is simple, without extreme graphic elements. She sticks as close to the poem as possible; the shift from one poem to the next is carried out using various kinds of interactivity made available to the viewer: by clicking on the double brackets (which sometimes play with the reader by not allowing themselves to be pinned down easily), panning across a word or symbol, moving the mouse, a soundscape, etc. Thus, around the famous poem a leaf falls on loneliness, she creates shifting landscapes of texts in the style of someone like Rognoni or Cangiullo - in keeping, therefore, with the 1920s, when many of cummings' poems were published - but revealing, in addition, the dynamic specificity of cummings' work. These landscapes grow richer, are modified, become more simple or complex as their reading progresses.

As a whole, they are very pleasant to read and very interesting also on the graphic level, even though I am not certain that I succeeded in exploring all their possibilities. I may even have missed some essential interactions.

Isn't this possibility of incompleteness, however, of taking another stab at it, of going back again and again, precisely one of the most interesting things about digital literature?

Jean-Pierre Balpe

(Translated from French by Timothy Barnard)

top top

back back

|

|

|

|

|

|