ISSUE 2 ⎯ MARCH 15, 2020

ISSUE 2 ⎯ MARCH 15, 2020ARTIFICIAL WORKS OF ART

____________________________

All about emerging artists exploring the creative power of AI

and the most prominent personalities in the field of AI and generative art.

DO ARTIFICIAL WORKS OF ART EXIST?

by Anne-Marie Boisvert

Composer and computer scientist David Cope is the creator of a computer program called Experiments in Musical Intelligence (EMI) that “composes” music from a database of pre-existing musical pieces. The program has proven capable of successfully creating musical works in the style of famous musicians from the past, such as Vivaldi, Bach and Beethoven. However, public reception was negative, as was that of the music community. Not because these “works” were unattractive, but because the revelation that a computer system was behind the works rather than a human was enough to discredit them. In other words, the status of “work of art” was immediately withdrawn. Rather, they have been seen as computer productions lacking in authenticity and uniqueness, infinitely multipliable and therefore without any real aesthetic value (see Boden and Edmonds 2009, p. 24 and Cheng 2009).

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kuY3BrmTfQ[/embedyt]

David Cope, Experiments in Musical Intelligence, Vivaldi

Definitions of a work of art

But what is a work of art? By way of definition, we could offer the following answer that seems to capture the most common conception of what a work of art is: a work of art is an artifact (as opposed to a natural entity) to which its creator intentionally conferred an aesthetic value, with the aim that this aesthetic value be grasped as such by the audience to which the work of art is addressed.

The key concepts here are those of “intentionality” and “aesthetic value”. First of all, what is intentionality? Well, intentionality is about intention, and means the will to do something. But in philosophy, the concept has a broader meaning: it designates the capacity for a mental state to be “about something” external to it. Beliefs, desires, intentions are examples of intentional mental states: I believe something, I desire something, I intend to do something. Note that this “something” is not necessarily a state of affairs of the existing world: I can believe or desire something that does not exist. For the record, the Austrian philosopher and psychologist Franz Brentano borrowed the concept from medieval philosophers like Thomas Aquinas and updated it at the end of the 19th century. The concept of intentionality has come to be considered in 20th century philosophy and psychology as the hallmark of the mind, that is, what distinguishes psychic from physical phenomena.

As for “aesthetic value”, it has been customary in the tradition to define it in terms of certain “aesthetic” properties that a work of art should be deemed to possess in order to be considered a work of art. These properties can be representational, formal and/or expressive: beauty, harmony, expressiveness, faithful representation, technical quality, originality… Their number and their nature can vary according to the definitions which are proposed. But the general idea is that the possession of at least some of these properties is essential for an artifact to be recognized as a work of art. And the aesthetic value of a work will depend on its greater or lesser success in achieving one or another of these properties. For example, the aesthetic value that will be given to a work may be a function of its greater or lesser representational fidelity, or of its ability to express a “truth”.

This type of definition was called into question in the 20th century. First, it has always been difficult, if not impossible, to agree on the number and nature of the necessary and sufficient properties that an artifact should have to be considered a work of art. Then new types of works of art appeared that did not seem to have any of the traditionally recognized aesthetic properties. The most obvious example is that of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades.

Marcel Duchamp, Urinoir, 1917

Other definitions of work of art have been proposed, like so-called institutional definitions, such as those of the American philosophers Arthur Danto or George Dickie. According to the latter, a work of art is an artefact “to which one or more persons acting on behalf of the art world have conferred the status of candidate for appreciation” (Dickie 1974). Dickie’s more recent definition consists of a set of five statements: “(1) An artist is a person who participates with understanding in the making of a work of art. (2) A work of art is an artifact of a kind created to be presented to an artworld public. (3) A public is a set of persons the members of which are prepared in some degree to understand an object which is presented to them. (4) The artworld is the totality of all artworld systems. (5) An artworld system is a framework for the presentation of a work of art by an artist to an artworld public ”(Dickie 1984, as presented by Adajian 2018).

French aesthetic philosopher Jean-Marie Schaeffer proposed a “pragmatic” definition of a work of art, based on four criteria (see Schaeffer 1996; see also Gibert 2020). First, an artifact will be considered a work of art if it can be placed in a recognized artistic genre: painting, sculpture, music, and more recently, installation, performance… This is what Schaeffer calls “generic belonging”. Schaeffer’s second criterion is that of the aesthetic attention given by an audience to the artifact which they perceive and receive “as” a work of art. Note that this criterion of “recognition” comes close to an institutional type definition such as that developed by Dickie: an artefact will be considered a work of art if it is recognized as a work of art by the art community, exhibited in a “serious” gallery and reviewed by art critics. Schaeffer’s third criterion is that of artistic intent. Duchamp’s urinal is a work of art because Duchamp so decided. Schaeffer’s fourth criterion is that of intentional causation. Intentional causation extends the artist’s simple intention. It comes from the concept of philosophical intentionality as it was defined above, that is to say the fact for a work to be about something, to mean something.

If we accept this definition in four criteria of the work of art, it seems that a work produced by an artificial intelligence system cannot be considered a work of art since it does not fulfill the last two criteria.

Computational generative art

British philosopher and psychologist Margaret A. Boden published in 2009 an article written jointly with British artist, computer scientist and theorist Ernest A. Edmonds, entitled “What Is Generative Art? ” In this article, the authors endeavor to provide a definition of what they call “computer-generated art” (CG-art for short) in order to distinguish it from another type of art with which it is often confused, namely computer-assisted art, which uses computers as mere tools. Both belong to a more encompassing type of art, called simply “computer art” by the authors. Too often all of these terms are commonly used to denote the entire field and are often treated as synonyms. These artistic practices make use of the communication and information processing technologies developed since the second half of the twentieth century. The resulting works of art are very diverse: visual arts, videos, music, multimedia installations, virtual reality, kinetic sculpture, robotics, performance and literature.

The authors begin by noting that the terms “generative art” and “computer art” have been used more or less interchangeably, since the first computer art exhibition by artist Georg Nees entitled “Generative Computergraphik” held in Stuttgart in February 1965. But generative works of art do not necessarily all use computers. And not all computer-based works of art are generative works of art. However, “in music and in visual art, the use of the term has now converged on work that has been produced by the activation of a set of rules and where the artist lets a computer system take over at least some of the decision-making (although, of course, the artist determines the rules)”(Boden and Edmonds 2009, p. 4). In section IV of their article, the authors propose a taxonomy of generative art according to eleven types of art, called Ele-art, C-art, CA-art, D-art, G-art, CG-art, Evo-art, R-art, I-art, CI-art and VR-art.

These eleven types of art are defined by the authors as follows:

(1) Ele-art (electronic art) involves electrical engineering and/or electronic technology.

(2) C-art (computer art) uses computers as part of the artistic creative process.

(3) D-art (digital art) uses any digital electronic technology.

(4) CA-art (computer-assisted art) uses the computer as an tool (in principle not essential) in the artistic creation process.

(5) G-art works (generative art) are generated, at least in part, by a process that is not under the direct control of the artist.

(6) CG-art (computer-generated art) results from some computer program being left to run by itself, with minimal or zero interference from a human being.

(7) Evo-art (evolutionary art) is developed by processes of random variation and selective reproduction that affect the art generating program itself. Evolutionary art is a sub-genre of computer-generated art.

(8) R-art (robotic art) is the construction of robots for artistic purposes, where robots are physical machines capable of movement and/or autonomous communication. Robotic art is also a sub-genre of computer-generated art.

(9) In I-art (interactive art), the form/content of the work of art is significantly affected by public behavior.

(10) In CI-art (interactive computer-generated art), the form/content of certain CG illustrations is significantly affected by public behavior. Interactive computational art is also a sub-genre of generative computational art according to the authors.

(11) In VR (virtual reality) art, the observer is immersed in a computer-generated virtual world, and experiences and responds to it as if this world were real.

(Boden and Edmonds 2009, p. 19).

The primary interest of this nomenclature for our purpose is to make the distinction between, on the one hand, artistic practices which use computers as tools, and on the other hand, artistic practices which belong to generative computational art, in which a computer system plays a role of creator (or co-creator).

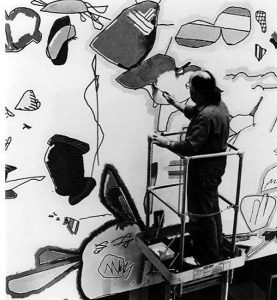

A well-known example of computer-generated art is David Cope’s EMI program discussed at the start of this article. Another example is AARON, a computer program written by artist Harold Cohen who is capable of creating original artistic images. AARON has been constantly evolving since 1973. Initial versions of AARON created abstract designs that became more complex in the 1970s. Figurative images were added in the 1980s.

Harold Cohen coloring the shapes produced by AARON at the Computer Museum, Boston, MA, ca. 1982. Collection of the Computer History Museum, 102627459.

A final example is that of the installation Galápagos, by the American artist Karl Sims, created in 1997. This work belongs to the sub-genre of evo-art described above. It is also interactive. The installation consists of a series of monitors resting on pedestals. Each of these monitors display 3D creatures generated by artificial evolution. Spectators were invited to place their feet on the mats placed in front of each monitor to select which of these creatures would be allowed to survive and access the next stage of evolution.

Karl Sims, Galápagos, 1997

In section V of their article, Boden and Edmonds examine the philosophical questions raised by computer-generated art (see Boden and Edmonds 2009, pp. 19-24). The big question is obviously this: is it really true that a computer can create its own works? Or does it always create only that of the programmer (artist), even indirectly? For example, “Was it AARON who generated these beautiful color drawings, or was it Cohen?” The latter admitted that he himself “wouldn’t have had the courage to use those colours”. But he also said he was happy that more of his works would continue to appear long after his death (Boden and Edmonds 2009, p. 20, citing Cohen 2002).

And the most obvious question remains: “is it really art?” ” Many people say no: according to them, computers do not create works but automatically generated “outputs”, lacking in authenticity and originality. From their point of view, art involves the expression and communication of human experience; therefore, a computer that is not an “emotional creature” cannot be the author of a work of art. It seems that Jean-Marie Shaeffer would support a similar position: because a non-emotional creature cannot meet the criteria of “artistic intention” and “emotional causation”, it cannot be an artist. Another common way of discrediting computer art in general is to say that art involves creativity and that no computer can really be creative. But what exactly does creativity mean? As Boden and Edmonds point out, creativity implies agency, that is to say the ability to act of a being, its capacity to act on the world, things and beings, to transform them or influence them. However, computer systems are often described as “intelligent agents”, able to capture and process information, either in the form of data (inputs), or directly from the world (thanks to sensors) and able to act on the world. The most intelligent artificial agents are even able to learn. But is that enough?

All these questions that we have only touched on here require development. We will continue this reflection in a future issue.

Bibliography:

Adajian, T, « The Definition of Art », Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2018.

Boden M. A. et E. A. Edmonds, « What Is Generative Art? », Digital Creativity, 2009, pp. 1-24.

Cheng, J. “Virtual Composer Makes Beautiful Music – and Stirs Controversy“, in Ars Technica, September 29, 2009.

Cohen, H. « A Million Millennial Medicis », in L. Candy and E. A. Edmonds (dir.), Explorations in Art and Technology, Londres, Springer, pp. 91-104, 2002.

Cope, D. Virtual Music: Computer Synthesis of Musical Style, Cambridge, Mass., MIT

Press, 2001.

Cornock, S., et Edmonds, E. A., « The Creative Process Where the Artist is Amplified or Superseded by the Computer », Leonardo, 6, 1973, pp. 11-16.

Dickie, G., Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1974.

Gibert, M, « L’oeuvre d’art artificielle : une disruption ontologique ? », Espace, hiver 2020, pp. 50-53.

Schaeffer, J-M, Les célibataires de l’art, Paris, Gallimard, 1996.

ALEXANDRE BURTON: A QUEBEC ARTIST IN AI ART

by Anne-Marie Boisvert

With the creation of the CIAC’s Electronic Magazine in 1997, the CIAC MTL offered a privileged showcase for digital works of art and their creators.

Read more

NEWS

Publication : Pierre HENRICHON, Big Data : faut-il avoir peur de son nombre ?, Éditions Écosociété, March 2020.

Read more